Founding a startup: How to Split Equity Among Co-founders?

Finding the right co-founder for a start-up is hard enough. The functioning of a partnership depends essentially on with how much equity the co-founder is involved in it. Because after all, it is the ownership of equity that matters to a founder.

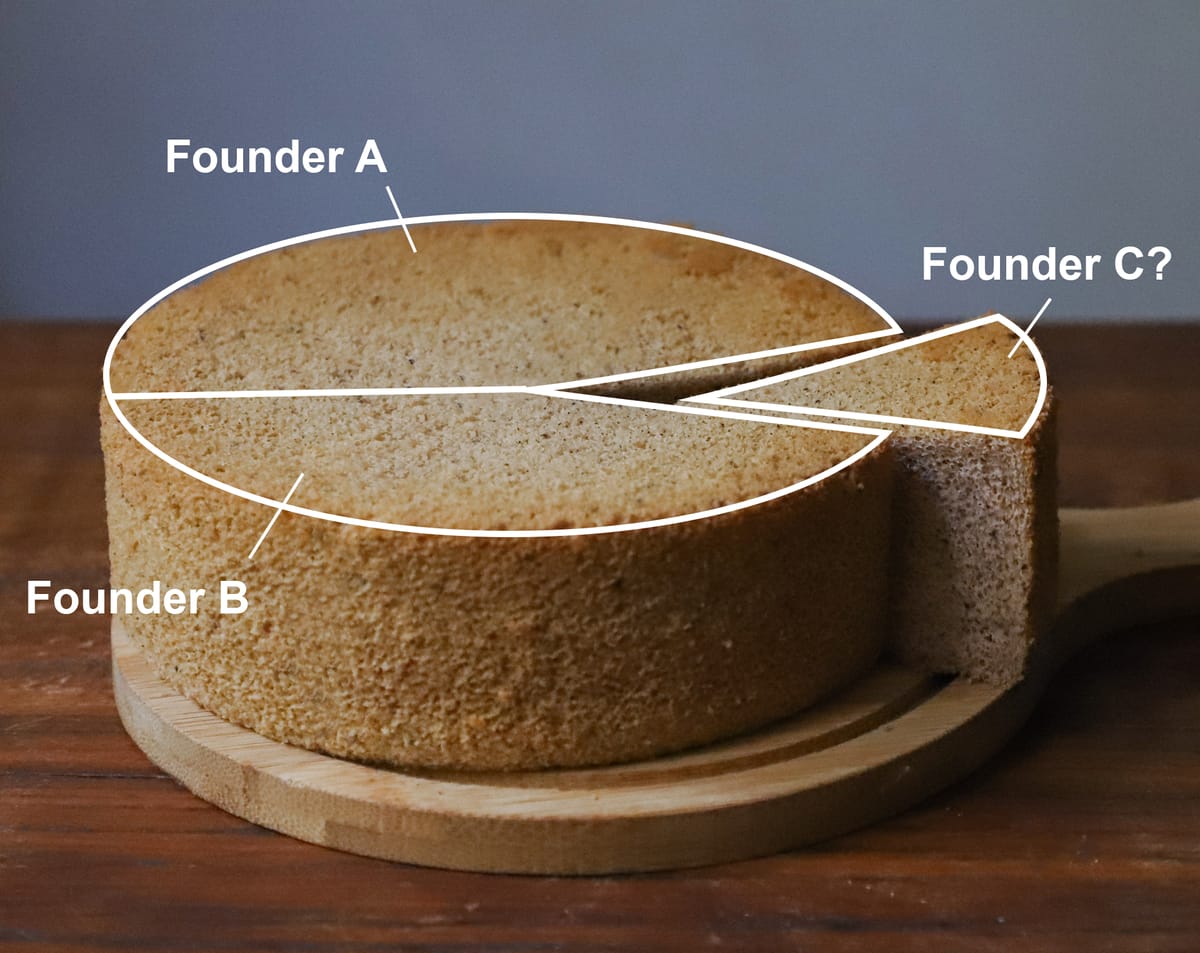

When we founded labfolder, we were three co-founders. We chose the easy way: We splitted equally, each 8334 shares or 33% of a GmbH (German Inc.) with an initial nominal capital of 25002 shares. After about two years, one co-founder left the company for understandable reasons.

A former co-founder who holds many shares is not only a nuisance for old and new investors, but also a major problem for the motivation of the remaining founders, because we three naturally imagined things differently at the beginning.

Everyone of us assumed that we would stay together as a team. Out of this naivety, we decided that everyone would get an equal share.

I do not mean that an even distribution is a bad solution because of this previous experience. I just learned not to be naïve about the distribution of shares.

Summarized, my learnings were:

- talk openly and transparently with all those involved,

- seek more external advice,

- compare better with what other founders and companies do,

- think longer about how much equity everyone should get and

- structure the split differently even before getting investors aboard.

What does that mean in detail?

Talk about equity as early as possible

Because equity is so important, the discussions about the distribution should be started as early as possible. This applies to the case in which you know your co-founder for a long time (e.g. from university), but also when you just recruited him or her.

After all, a good co-founder is characterized by the fact that you can talk to him openly. Anyone who postpones the conversation about shares, e.g. on the grounds that "there is nothing to distribute", is either not interested in the business aspect of founding a company, or he or she is generally reluctant to deal with difficult issues.

Especially as an initiator, as the guy who had the idea and drives it forward, you should be actively seeking the conversation. Start the conversation long before you officially incorporate the company. Start it before you are looking for investors, before money is on the table.

It is much easier to talk about the overall structure, about roles and contributions of co-founders, if there's still nothing to distribute. If there are already first successes and money on the table, there is a greater risk that the distribution is governed by greed and not by reason. It is the responsibility of the initiator(s) to mitigate risks and to remove blockers at an early stage. And not talking about equity is such a risk, something that can turn into a big show stopper later on.

How much equity should you keep for yourself as an initiator?

As an initiator, you may feel like a beggar to potential co-founders. In this very early stage you have to convince everyone of your idea. And you have to convince potential co-founders so well that, for example, they give up a secure, well-paid job.

However, as an initiator you should always make it clear to yourself that even years after starting the company you may still have to stand up for the idea and for the company more than anyone else. Of course a good startup team naturally develops so many ideas together that sooner or later it's not a single person’s thing anymore, but really their company, their product, their innovative thinking. But still, as the initiator you feel a bit more responsible for it.

Not that it would be said out loud: Especially at the beginning and whenever something goes wrong (and it certainly does, frequently!) the initiator often feels like the others secretly pointing the finger at him and thinking "This guy had the idea, this guy is to blame".

Of course you can argue that as an initiator you are always in the spotlight when things go well. But a good founder should act according to the maxim: Distribute the glory among all, take responsibility for everything.

In this respect, it is not greedy to hold at least a symbolic majority as an initiator. Any good co-founder will understand that.

Giving out shares to a co-founder is an opportunity

As an initiator, giving out shares should always be seen as an opportunity. As an opportunity to take shareholders on board who can contribute something. This applies to co-founders, important employees and investors.

You have a good, capable friend who likes your idea and maybe wants to join? This is an opportunity! Ask him about his expectations in terms of equity. Listen to him, how he imagines working together, but also the distribution of shares.

You get to know someone who has a great job, but would maybe like to get involved in a start-up? A huge chance! Give her the opportunity to express her expectations. Make it clear from the start that equity is involved and that you are willing to talk openly about her share from the start.

This does not mean that you have to agree on the exact distribution as soon as possible. But the discussion about the topic should be started as soon as possible.

What does the distribution of equity depend on?

First of all, a span: what does "a lot of equity" and "little equity" actually mean?

"A lot of equity" means: the same share as you as initiator. I would only offer the same or similar equity to co-founders who are actively involved in the idea, who are committed long before the incorporation (more than half a year) and who can and want to invest time without expecting a compensation. These co-founders are actually co-initiators. Through their commitment they show creativity, the necessary "burning for the idea" and resilience. My labfolder co-founder Florian is such a person and I am extremely happy to have found such a co-founder.

As a measure for very, very little equity should serve the example of a consultant consultants or "hands-on supporters" who will never and certainly not full-time work in the company, but who help with important tasks, actively contribute a large network, and who motivate, coach and advise the founders.

For everything in between, probably no one can define concrete rules. The final distribution always depends on many factors, for example:

- How long did you work on the idea before co-founders joined?

- Can a co-founder contribute in the pre-start-up phase and in day-to-day operations?

- How critical is the co-founder with regard to: How well does he complement your skills?

- Is there demand on the market for the skills and experiences the co-founder contributes?

- Which "soft" factors does the co-founder contribute; network, coaching and consulting skills, etc.?

- What is the funding situation like at the time when the co-founder joins? Is there a lot of money and therefore the risk relatively low or does money have to be raised soon?

How well you get along with a potential co-founder should not be a factor for the distribution. It is the most essential factor ever - if the chemistry is not right, you should not talk about starting a business together. At some point you are always disappointed by someone. Or even two or three times. I don't know any founder who hasn’t been disappointed by co-founders, trusted employees or business partners. And that includes me.

But that's exactly why I say all the more today that you should pay attention to your gut feeling. Don’t give equity to anyone where you feel the chemistry might lead to an explosion.

How much to give? A few rough guidelines from my experience.

There is no set of rules how equity should be distributed. What can be considered "a lot" and what feels "little" in between the span outlined above varies from case to case.

Here a few guideline values from the point of view of an initiating founder or a team of initiating founders:

| initial founder team size | 1 initial founder | 2 initial founders | |||

| final founder team size | 2 | 3 | |||

| Co-founder gets ... Co-Co- | founder% | Initial founder% | founder% | Initial founders % | Co-founder vs. founder shares |

| very, very little equity | 2.5% | 1.7% 98% | 98% | Co-founder gets 1/20 of the initial founder shares | |

| very little equity | 5.0% | 3.3% 95% | 97% | Co-founder gets 1/10 of the initial founder shares | |

| little equity | 12.5% | 88% | 8.3% | 92% | Co-founder gets 1/4 of the initial founder shares |

| decent amount of equity equity | 11.1% | 16.7%83% | 89% | Co-founder gets 1/3 of the initial founder shares | |

| high amount of equity | 25.0% | 75% | 16.7% | 83% | Co-founder gets 1/2 of the initial founder shares |

| Very high amount of equity | 33.3% | 67% | 22.2% | 78% | Co-founder gets 1/3 of the initial founder shares |

| Very, very high amount of equity | 50.0% | 50% | 33.3% | 67% | Co-founder gets the same amount as the initial founder (s) |

For example, read: "co-founder gets high amount of equity" means for an initiating team of 2 founders: 16.7% Please note that this table only applies if there are no other shareholders aboard yet (e.g. business angels).

What types of co-founders exist and how much equity should they get?

Here are a few case studies:

Co-founders does not want to work 100%

Everybody has to earn his living and not everyone wants to give up everything else immediately. This is completely understandable.

In this case, you could initially give out a few shares only, and then conditionally go to a higher percentage, e.g. if the co-founder starts full-time. It may be possible to agree on this when establishing the company (as a kind of "conditional cliff", see chapter "Cliff"), but it is also a manageable effort to transfer shares back and forth after incorporation and before the first round of financing, if there has been no valuation in the meantime. Then the only costs involved are the fees of the notary and the lawyer.

In any case, this means that the co-founder only receives the final share, her "final value" once she gets 100% involved. If she only wants to work for the company temporarily in the long run, this is worth a small, <5% share. Then her work should rather be compensated with a consulting agreement or similar.

You yourself can not start 100%, but the co-founder does

It may also happen that you are an initiator, but you can't get involved 100% in the company from the start. You have to make a living, you have another company... there are thousands of reasons why a full-time involvement may not be possible immediately.

Depending on how long this period of time lasts, the co-founder, who is in at 100% from the start, is naturally entitled to receive a higher share. As for example a commercial co-founder, who brings a lot of experience and a great network and who perfectly complements you as a technical co-founder. Although you have already worked on the product or the IP behind the product for three years, you won't be able to start fully for another year. At the same time, the co-founder gives up a good job, so he takes a relatively greater risk. In this case I would say that the co-founder is entitled to a very high to very, very high amount of equity.

What makes a difference here is the funding situation: Did you already establish contacts to investors without the co-founder's involvement, is there perhaps already a funding program from which the co-founder can receive a salary?

Then the risk is significantly lowered and co-founding the company is actually a huge opportunity for the newcomer even if the company fails. He’s not taking a great financial risk, but in any case increases the value of his CV.

Technical co-founder

In principle, technical co-founders are not only share-driven. If your idea is innovative and interesting technology is to be developed, this matters a lot for a technical co-founder. At the same time, for a good technical co-founder, shares usually count more than salary, because she can probably earn more everywhere else, but would hardly get any shares. In the event that you offer innovative technologies and find an experienced CTO who wants to get involved immediately, I would consider to give out a very high amount of equity or even more.

If you are technically proficient yourself, can lead the product, and need a lead developer to help you implement and lead the tech team, a low to normal amount of equity is probably appropriate.

Commercial co-founder

As a counterexample, you might have a strong technical background but are relatively blank on the commercial side. You need someone who can come up with a good going to market strategy and, above all, can implement it. You need someone who designs the pricing, conducts market research and takes care of sales.

A note here: You should not look for someone who "does the numbers for you", i.e. bookkeeping - that is a mere administrative task and does not justify, on its own, to receive equity of the company. In principle, co-founders always need to be creative, i.e. they need to be able to move things forward in a creative way and not just administer them.

In the same way, you should not look for someone who "gets you the cash you need", i.e. takes over the fundraising. Although it makes perfect sense to look for strong support from a commercial co-founder here, it is a misconception that fundraising can be taken over completely by someone else than the founders. As a founder you are always involved in fundraising, especially at the beginning.

In my opinion, experience, enthusiasm for the product and demand on the market are very important factors to decide of how much equity to give to a commercial co-founders.

When it comes to experience, I think experience in the start-up environment is very important, a mixture of experience with larger start-ups and small start-ups (possibly also on the investor's side) is ideal and definitely more valuable than experience in a corporation or a strategy consultancy.

As far as the market is concerned, my experience is that commercial co-founders are easier to find than technical co-founders, although of course it is also true that good people are always in demand.

This means: If you find a good commercial co-founder, who has some relevant experience, but you have a lot of time and opportunities to keep on recruiting, I would consider a small to normal amount of equity. However, if there is someone knocking at the door who has a lot of experience, has many other options but who is fired up on your product right from the start, it might even be worth a lot of shares.

What do the others say? How many to split equity?

The article "Splitting equity with your co-founder? Here's what you need to know " provides a couple of sample questions to help you understand the value of a potential co-founder and thus the distribution of shares. Furthermore - and that's why the article is really worth reading - the author summarizes a few opinions on the subject, including those of Kevin Systrom (ex-CEO Instagram) and Michael Seibel, the CEO of Y Combinator.

Michael Seibel describes in his article "How to Split Equity Among Co-Founders" that when starting to distribute equity, many founders look too much at what happened in the first year of the foundation and not what has to happen in the seven to ten years it typically takes to build a successful company. According to him, since the future outweighs the past, the founding team should distribute the shares as fairly as possible. Definitely worth reading!

In "How Much of Your Company Should You Give New Co-Founders?" , Martin Zwilling does not take the opposite view when he writes: "to split everything equally to keep peace in the family is a terrible answer. Since then now no one is in control, and startups need a clear leader." What is meant here is that an equal distribution for sake of "peace and harmony" reveals lack of leadership. A founding team with leadership competence would actively address potential conflicts.

And that’s what I cannot repeat often enough: Deal with those issues as early as possible, handle it intensively, transparently, fairly and pragmatically. It is up to the initial founder or the founder_CEO role to get this topic on the table and off the table.

There are also a few tools that can help you calculate a possible distribution of shares by asking questions and evaluating answers. I tried the "StartupEquity Calculator" by foundrs.com and must say that the results are quite acceptable.

[caption id="attachment_189" align="alignright" width="660"]

Startup Equity Calculator by foundrs.com[/caption]

But to repeat it once again: there is no right answer to share sharing, there is only one right process how to handle the issue.

How to protect yourself when distributing equity

The process of allocating shares also includes taking precautions. Here is a brief outline of the methods and instruments available at your disposal:

Reference Calls

If you have recruited the potential co-founder (i.e. you don’t know him hor her for years), be sure to talk to people who have worked closely with him or her before. Ask for references and ask those references also about the uncomfortable things - such as to his or her weaknesses, where he or she failed etc.

Even if you want to start a business with a friend, talk to mutual friends about the idea of starting a business together. Get external opinions as to who will play what role in the planned company and what weaknesses and strengths each individual has.

Just be aware that you are entering into a kind of marriage with the establishment of a company. So you want to know very well who you are marrying. It is also not uncommon for friendships to shatter in a joint venture - your chances are good that you can prevent this by consulting someone external before you head out for business together.

Good Feeling in the Negotiation

There should be a positive atmosphere on both sides when talking about splitting equity. You should simply feel that the issue is important to your partner in terms of fairness, motivation and structure. You should feel that he or she treats his or her own shares as secondary to the common good, presents realistic ideas, and is acting pragmatically.

In other words: Someone who negotiates his shares extremely hard and you have the feeling that he wants to get the most out of the negotiation only for himself is not for the best foundation of building something together. Someone who renegotiates on the grounds of "At the first negotiation I didn't know how much work such a startup is" you should kick out immediately.

Of course, a "good feeling" is always subjective. Try looking at it from another angle: From my own experience, I can say that there is a “bad feeling” when you go to bed brooding over a co-founder several evenings in a row.

Vesting

Vesting and cliff are instruments to protect a company against the early break-up of the founding team.

To start right away with an example: Founders A and B should each receive 12,000 shares. They agree on a quarterly vesting over a period of four years.

This means that each quarter 750 shares accrue to each of the founders: 12000 shares are allotted, per year 3000 accrue, meaning each quarter accrue 750.

If a co-founder leaves the company after 10 months, he has accrued shares for three quarters of the year, i.e. 2250. When leaving he retains these shares and has to return the rest to the company.

Cliff

A cliff is an instrument used to enhance the vesting agreement. Let's stick with the example: Founders A and B agree on a cliff of one year in addition to the above-mentioned vesting. This means that within this year no shares will accrue at all, but at the end of this year all the shares that would have accrue by then according to the vesting arrangements will accrue in one go.

So if a co-founder leaves the company after 10 months as described above, she has no right to keep the equity and needs to return all his shares to the company.

However if she stays, she will have 3000 shares in month 13, at the end of the cliff year.

If she then would leave the company in month 16, she would have accrued 3750 shares.

[caption id="attachment_191" align="alignright" width="660"]

Vesting Scheme: 12,000 shares are allotted to each founder, but because of the structures, each one accrues only 750 shares quarterly. Without cliff, the shares accrue from the beginning. With cliff the shares accrue to 3750 after one year, after that the vesting scheme continues as the one without cliff.[/caption]

Vesting and Cliff: what is usual?

Vesting regulations are usually made for the founding team as soon as investors get on board.

This is completely understandable: the founding team is both the most valuable asset as well as the biggest risk of the company, especially at the beginning. Founding teams simply break apart often, and new shareholders want to protect themselves against this as much as possible.

With regard to vesting, I have seen terms between three and five years and both quarterly and annual vesting.

I have seen one to two years for Cliffs.

This is what a good and fair arrangement among co-founders would look like to me:

- Vesting over 4 years

- Quarterly Vesting

- Cliff of 1 year

How to deal with Vesting and Cliff in terms of a co-founder?

As far as I know, it is not usual for founders to make vesting and cliff agreements before other shareholders join in. However, I would strongly recommend it! The simple reason: It facilitates the negotiation. If there is a safety net, it is easier to take the decision to jump together.

Imagine the case of a co-founder having been recruited. You're working well together, but you only know each other for half a year. Now it's time to start a company and the issue of splitting equity becomes an issue. No matter how well you get along, you are about to enter into a marriage-like relationship that should last at least 7-10 years. It is absolutely understandable that it makes you wonder whether six months is enough to enter into such a partnership. Agreeing on vesting and cliff rules simply gives everyone more time.

That’s why I also believe that the same rules should apply to everyone involved, initiating founder and co-founders: Vesting and Cliff are for getting to know each other, for protection against disappointments and for keeping up motivation.

If you treat vesting and cliff as early and as openly as the distribution of shares, it can make the whole process faster and easier.

Be pragmatic

Last advice: Don't make a science out of the distribution of shares.

After all, it is of course true that you distribute the booty before the battle is fought. Of course, this does not mean that the issue should be postponed. But you should also not negotiate too long about it and structure yourself to death.

You should discuss the topic openly with the potential co-founder and then come to the conclusion of what distributions everyone would be happy with so that you wouldn't have to talk about it anymore in the future. If you don't get to that point, you should pragmatically agree on something that is acceptable to everyone for at least for the next year or until a certain event (e.g. investor joins in). If other shareholders are open to it, one can also issue further (virtual) shares later in course of a employee stock option program.

It is nerve-wracking for the founders if a potential co-founder always wants to renegotiate. In the same way it is nerve-wracking for a co-founder if the topic of participation is postponed further and further by the initial founders.

Therefore: Deal with the topic openly and transparently, but then also just close it at some point.